Libyans have written their own story, and it is a good one. After nonviolent protesters were massacred across the country in February, a widespread uprising finally coalesced into victory yesterday. Benghazi became the geographic center of rebellion on February 20th; using social media, Libyans there immediately cried out for international intervention. That assistance arrived in the nick of time, with NATO establishing immediate air and sea supremacy. The next six months saw freedom fighters and their international allies organize an AirLandSea campaign of combined arms, maneuver, and insurgency.

CAUSES

The Chomskyan narrative frame of empire and power has little real application to the outbreak of conflict in Libya. I have written before about the causes, but the most important single thing to understand is that about seventy percent of the North African diet is bread. Climate-change driven drought in Russia last Summer raised global wheat prices across the region over the Winter. In a region with sluggish GDP growth, that has created social alarm.

Food insecurity is a common cause of conflict (.PDF) and the most common cause of conflict in the region (see: Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, Sudan, Chad). Wars rarely solve food insecurity, however, and the conditions that brought conflict to the North African maghreb have only intensified since February. We live in interesting times.

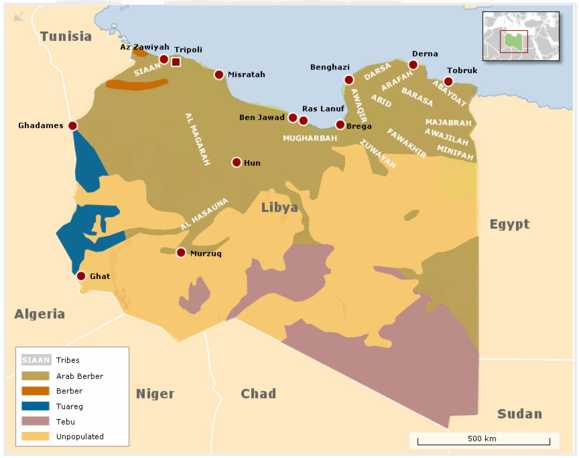

The tribal structure of Libyan society also plays a role. Moammar Ghadafi has been playing the tribes against one another for four decades, and it has finally caught up with him. On this map, you can see one of the disaffected Berber tribes to the southwest of Tripoli, along the Nafusa Mountain escarpment. They are among the most persecuted minorities in the country:

In this map, you can see the location of another tribal group: the powerful Warfalla, centered around the city of Bani Walid, has also played a key role in the Libyan story. Ghadafi came to regret massacres in Bani Walid; despite his attempts to woo them back to his side, tribal leadership wavered throughout the Spring and turned against him during the Summer. Located between the rebel stronghold of Misrata and the Berbers of Nafusa, they would later play an important part in cutting off Tripoli.

One more cause needs to be named: water insecurity. Water rights have been a major source of Ghadafi's tribal power system. Advancing desertification (again, climate-change driven) has compounded both tribal resentments and food insecurity. Ghadafi's much-ballyhooed 26-year long water project is unsustainable. By draining a nonrenewable supply of fossil water, the project promises the same long-term outcome as Saudi Arabia's fossil water project: after three decades of self-sufficiency in wheat production, their water is running out -- and the kingdom has switched to importing wheat again.

These insecurities set the stage for the Arab Spring in North Africa. The spark in Tunisia spread to Cairo, then Libya, because these countries were tinder-dry powder kegs waiting to be lit.

OBJECTIVES

Of course, oil figures large in the conflict -- but not as a cause. Indeed, the oil industry can expect to spend at least months, if not years, ramping production levels back to prewar levels. The conflict has not served the hydrocarbon industry in any appreciable way. However, gasoline figures large in military logistics: tanks and trucks need fuel to bring firepower within range of the enemy. Rommel's Afrika Corps lost their war in this same stretch of desert when they ran out of fuel.

Naturally, Libya's petroleum infrastructure has provided many of the war's primary objectives and battlefields. The capture of the refinery at Zawiya last week proved the fatal blow to regime power in Tripoli, as gasoline supplies in the capitol were already low and forces could no longer be motored to the fight.

Below, a map of oilfield distribution within Libya. With most of the country's pumps in the Eastern half, the Transitional National Council began the conflict with a working refinery at Tobruk and most of the nation's oil resources either in hand or within reach.

This situation produced a raiding style of warfare in the East, but it also limited Ghadafi's ability to maintain offensives. He proved unwilling to destroy these contested wells and pumps; instead, the raids were about denial -- leaving the infrastructure booby-trapped instead of damaged. Ghadafi was more than willing to attack and destroy fuel infrastructure firmly within rebel territory, while NATO planes have unapologetically targeted his supplies of gasoline.

Objectives often determine the forces. Most of the war has been fought with "technicals" -- converted pickup trucks. While these vehicles have been the object of admiring reportage about a "ragtag" army, in fact the technical was invented by Chadians during their Toyota War with Ghadafi in 1986 -- outrunning and outmaneuvering his very expensive Russian-built tanks to attack them with shoulder-fired rockets. The open desert rewards fast movement, so technicals have proven the mainstay weapon of the war for both sides.

ALLIES

Objectives are also driven by policy. After the initial phase in which NATO forces established air and sea supremacy, the first six weeks of Operation Odyssey Dawn focused on destroying command and control centers as well as mass concentrations of government armor and heavy weapons. This phase saw European allies burning through their stockpiles of precision munitions so quickly that observers lamented their unpreparedness. Indeed, by April the Euroskeptics (including yours truly) were calling for an end to Western Europe's free ride on American firepower.

Yet Odyssey Dawn has been a truly international effort, a fact recognized by the freedom fighters in rows of allied national flags (including, importantly, the United States). The international nature of the war, for better or worse, is exactly what has driven neocons bonkers. Furthermore, the air campaign has been extremely judicious -- too much so for Senator John McCain, who raged against NATO multilateralism and advised a go-it-alone strategy of increased American firepower.

By late May, Western special forces were operating in Libya. Rather than engage in combat, they mainly served as eyes on the ground; half of modern war is just finding out what the hell is going on. Where is the fighting? What are the conditions? What is the terrain? Together with human and electronic intelligence, this information provides commanders with a clearer picture of where and how air power can be applied.

Close air support is not easy. It is even harder to do in a supersonic jet, and depends largely on ground-to-air communication. The most underreported aspect of the Libyan conflict has been the outsize contribution of drones, which have replaced the need for a common radio net with their ability to linger for hours, even days, over target areas to monitor movement and identify targets.

Unmanned Arial Vehicles provided the best air support of the war, earning praise from the Libyans. Each escalation by the United States involved more UAVs. They are fast becoming the most revolutionary weapon in the American arsenal, and Libya will probably be seen one day as the beginning of the end of manned combat flight.

The Western Allies also advanced the Transitional National Council by recognizing it as the legitimate government of Libya. Especially in the last two months, Ghadafi has faced a series of new "facts on the ground" as Russia, China, Europe, and the United States shifted their national diplomatic contacts to the TNC, culminating last week in the handover of Libya's US embassy.

Last, but certainly not least, supplies of arms and equipment have reached the rebels. At least two countries, Qatar and France, have done so quite openly.

PHASES

After the early campaign, US forces remained "over the horizon" while the popular rebellion attempted its first offensives. In the closing days of March, resurgent freedom fighters dashed along the coastal road towards Ghadafi's stronghold of Sirte (alt. Surt). This is my own map of that first offensive phase:

However, the rapid advance stalled before Sirte when loyalist forces counterattacked. Fighters' lack of training and coordination told in a disorganized retreat back to Ajdabiya, where the rest of the war would see a battle of attrition before the loyalist defenses at Brega. While indecisive -- and largely to blame for the media's narrative of a static, futile conflict -- the main achievement of this phase was to tie down lots of loyalist troops in the East.

This created space for advance by maneuver. During the second offensive phase, with Ghadafi's forces at Sirte unable to turn on Misratah, the TNC moved troops and supplies to relieve the besieged city:

This action circumvented the long coastal road and Sirte by moving through space denied to Ghadafi's navy -- an application of maneuver warfare theory that took advantage of the allies' control of the sea. It would be repeated in the fall of Tripoli later. Mind you, the kill boxes on my map are likely to look nothing like the ones on operational maps used by any American commander; they merely represent another trend of this phase, as NATO strikes were stepped up again.

The loudest, best-known airstrikes were in Tripoli, especially Ghadafi's command-and-control bunkers at Bab al-Aziziya. Yet out in the hinterland, a sustained and effective targeting campaign (aided especially by the arrival of the first drones) was pounding armories, armor, and heavy weapons -- producing scenes of destruction for Berber tribesmen to gawk over as they pressed Ghadafi from the south.

Indeed, by the middle of May a whole new front had appeared on what I call "the Wazan Line." The people living along the escarpment of the Nafusa Mountains defeated Ghadafi's forces from high ground, capturing the border crossing at Nalut on May 21st. This Western fight proved to be the most important one of all. By early July, the door was already swinging shut on Ghadafi, with the vital crossroads at Gharyan under rebel eyes:

It was during this third offensive phase, as the Misrata beachhead expanded and the Warfalla tribe turned against Ghadafi, that loyalist units began to crack under the strain. Demoralized, abandoned by commanders, soldiers started defecting and deserting. Operations began to take on their own momentum. Before July was over, freedom fighters had enveloped Brega. Ghadafi's raids on Eastern oil infrastructure ceased for lack of fuel. In fact, there had been no sustained offensive by loyalists since April.

The fourth offensive phase saw the Berber tribesmen descend on Gharyan, cutting the pipeline to Zawiyah and then advancing to take that city and cut off Tripoli from Tunisia. With the Warfalla to the south and Misrata to the East, Ghadafi was effectively surrounded by early last week. The fifth phase would be the most daring one yet, and involve the most clear uses of insurgency doctrine since the war's beginning.

Sometime after dark on Saturday, hundreds (perhaps one thousand) fighters arrived at the shores of Tripoli in Zodiac boats. They carried guns and ammunition for an apparently-large underground within the city that had been patiently awaiting this moment. Having linked up, the freedom fighters fanned out across the city to erupt in many places at once. This map was crowdsourced by Libyan tweeters:

The confusion and chaos kept security forces pinned inside Tripoli as rebels advanced from South and East. By yesterday afternoon, they were overrunning Mitiga airbase as they blew past the city limits, finding it deserted. Despite pockets of continued resistance, liberators continued streaming into the city long past nightfall in a pattern familiar to anyone who has studied the fall of Saigon. A numerically and materially inferior force has overcome its weaknesses with well-coordinated, effective planning.

CONCLUSIONS

Two myths should be put to rest. First, the idea that Libya's war originated as anything but a native conflict is nothing but paranoid speculation. Indeed, freedom fighters have systematically ignored international sanctimony and calls for a cease-fire. Libyans fought, and appear to have won, their own war, following their own plan. That they had help -- from the sky, or via Egypt, or by sea -- does not detract from the sacrifices of Libyans who refused to stop fighting and dying. They own their victory.

Second, the image of "ragtag revolutionaries" is also false. Freedom fighters have in fact been consistently clever and creative. While still undisciplined tactically, they have demonstrated good operational discipline and planning, and in fact have done a very good job of coordinating with air power despite the challenges. Never wavering in determination, Libyans have written their own epic, and it is a good one. All the allies did was help.

Cross-posted from Osborne Ink, where I have been keeping up with events.