Monica Duffy Toft, Tufts University

What happens to a country when its core national identity – its preferred image of itself in terms of race or religion – doesn’t match its demographic reality?

Say a Sunni-dominated Arab country is actually a majority Shi'a Arab country; or a Russian-Slavic majority becomes a minority; or a white Protestant U.S. becomes predominantly mixed race and mixed faith.

The answer, unfortunately, is “nothing good.” Internal strife, perhaps civil war or collapse often precedes a decisive demographic shift. Let me explain.

My research looks at what happens when countries cherish a central national identity – invariably made up and maintained by groups in power – and that identity is challenged by the reality of differential demographic growth rates.

Rather than face “identicide,” most representatives of that mythic identity will fight back, either subtly or with violence.

Consider the most important example in recent memory: the relatively peaceful disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991.

The USSR then

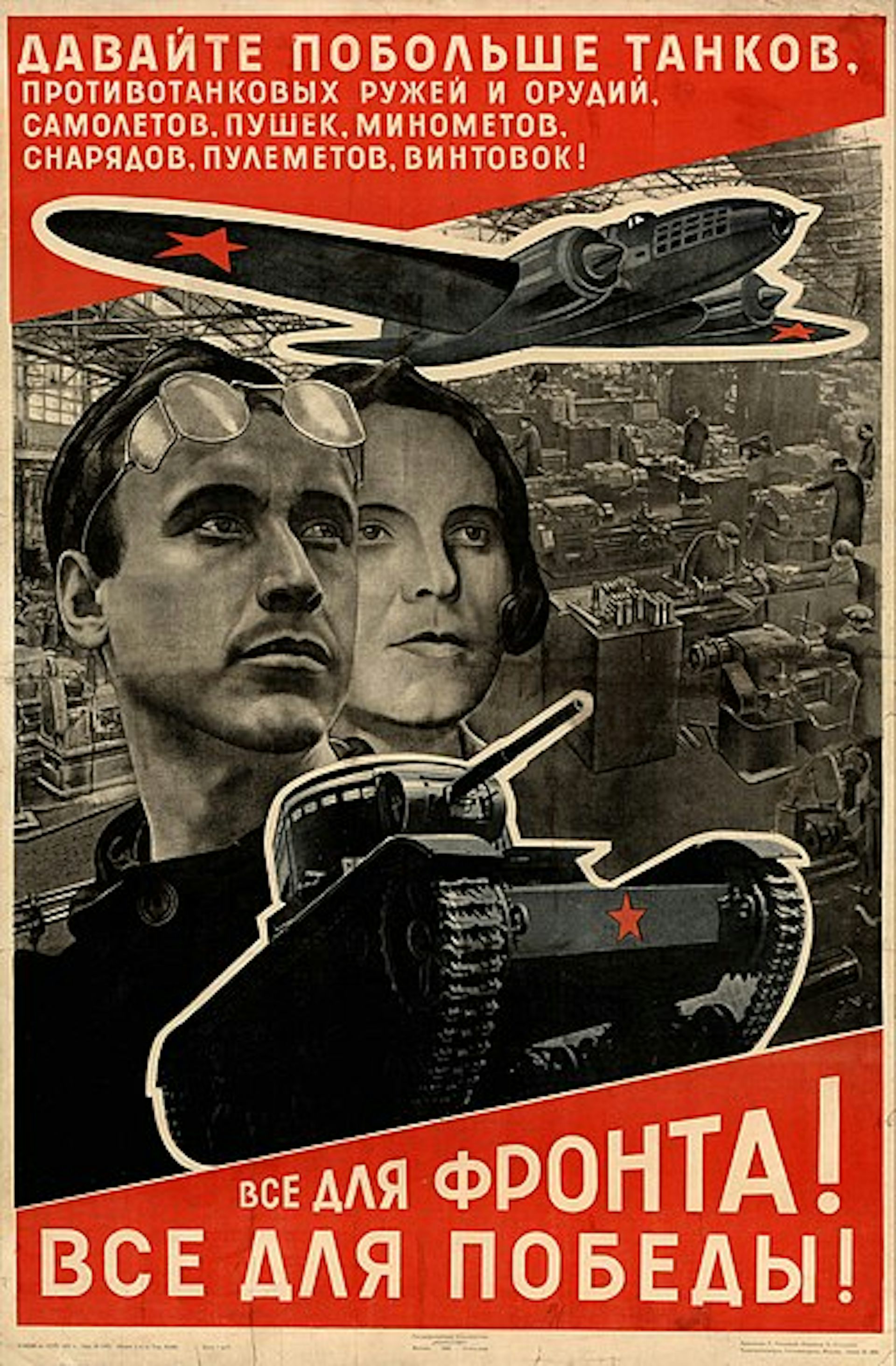

The Soviet Union’s mythology and national identity narratives tended to produce heroes who were Russian Slavs, including literary figures, military heroes, cosmonauts, political elites and Olympic athletes.

Although the image projected was Slav, if not Russian, the Soviet Union was in fact home to hundreds of distinct ethnic, linguistic, racial and religious groups. But as George Orwell might have quipped, in the Soviet Union, all ethnic groups were equal, “but some ethnic groups (Russian Slavs) were more equal than others.”

This proved ironic in two senses. First, much of this Russian Slav heroic narrative was constructed under the leadership of an ethnic Georgian, Josef Stalin.

Second, after World War II, Soviet census data began to record an alarming trend. Slavs, concentrated in major urban areas with access to higher education and employment, were not having nearly as many babies as Chechens, Kazakhs, Tatars and Uzbeks.

At the same time, the life expectancy of Slavic males began dropping due to widespread alcoholism, and accidents and diseases related to alcoholism. This made their female partners, most of whom were also employed full-time, somewhat reluctant to start or expand families.

At first, the actual demographic statistics were simply falsified for public release – a very common practice in authoritarian countries. But, by the mid-1970s, the demographic demise of the USSR’s Slav majority had become a state secret and a major policy concern; and even more so with the conclusion of the 1979 census, the results of which were not published for five years.

Government efforts to improve the birthrate of Slavic women and dampen the birthrate of non-Slavs came with unanticipated risks. By the 1970s, women from all ethnic groups had risen to become economically productive workers. Attempts to encourage Slavic women to marry young and have three or four children would have undermined the already fragile Soviet economic productivity.

Meanwhile, an impossible-to-win war in Afghanistan only made things worse. Post-traumatic stress disorder, heroin and opium abuse among young men added to the scourge of alcoholism. Citizens increasingly resented discrimination in education, employment and relocation permission for non-Slavs.

To both foreigners and Soviet citizens of all groups, the USSR looked like a majority Russian, Slavic country with little intermixing and intermarriage among the Muslim and non-Muslim populations. Only the Politburo knew that it soon wouldn’t be.

The USSR’s collapse

The Politburo faced intensified pressure for economic reform, partly to keep up with the West, but partly to free Slavic women to have more babies. This pressure led to the ascent of the young economic reformer, Mikhail Gorbachev.

Gorbachev, a lawyer by training and a true believer in communism, came to settle on two core policies to revitalize the Soviet economy: openness and restructuring.

Openness was intended to allow workers, planners and academics to work together to share best practices – but this merely made all Soviets more miserable. As the availability of knowledge of the outside world expanded, Soviets learned that none of the party’s longstanding claims about Soviet technology, education, health care and standard of living was true. Non-Slavs became aware of just how much their heroes, traditions, languages and histories had been unfairly left out of the Soviet national identity.

The resulting resentment would have been manageable, had not Gorbachev combined openness with “restructuring.” This gave political voice to what had formerly been low-level political and managerial positions and created a pathway for demographic injustice to express itself politically.

Non-Slavs began to use their new access to the political process to seek greater access to education, employment and residency in Russia’s major cities. Their demands were rebuffed, and the resentment grew only more intense, giving rise to nationalism and nationalist movements across the USSR.

The result was a crucial moment in Gorbachev’s leadership. In Tatarstan, Chechnya, Kazakhstan, the Baltic states and even Ukraine, there was talk of a reassessment of relations with Moscow – even possibly independence.

As resentment began to pull the Soviet Union apart, Gorbachev faced a stark choice between continuing to hope the Soviet ship of state would right itself, and the long-established practice of using Interior Ministry troops to murder protesters at mass rallies. Gorbachev chose the former, and the USSR disintegrated largely without bloodshed.

The US today

As you read your next depressing news report highlighting America’s polarization, even on the most basic of facts or growing lack of civility in political discourse, remember that historically these are due to a declining majority’s fear of losing “everything” in a democratic country in which groups vote as demographic blocs.

As with the Soviet Union, the U.S. too has a national mythology: one centered on an identity with a white, male and predominantly Protestant Christian hero.

This white, male, Christian identity was historically leavened with another point of pride, symbolized most poignantly by the Statue of Liberty. The U.S. has long celebrated itself for being big enough – in its space and in its economic system – to welcome immigrants; and our form of government made possible our greatest national strength: “out of many, one.”

For many Americans on the political right, however, a key question has become: Is the U.S. still big enough? Whites are still a majority across the country as a whole, but young people today no longer worry about mixing races or faiths. What will happen midcentury, conservatives wonder, when whites are no longer a majority?

The U.S. Republican Party has become a minority party, composed increasingly of older white Protestant males. Its base constituency feels threatened by what they’ve been told is an invasion of people who are making the country dirtier and poorer.

A February survey from the Public Religion Research Institute revealed that only 29% of Republicans preferred a mostly ethnically diverse country and 12% a mostly religiously diverse country. Such views on diversity encourage those who lean Republican to stay engaged politically, while their younger, mixed-race, multi-faith, majority Democratic and independent rivals’ constituencies often skip voting.

Left unmolested, rising identity groups rarely vote as a bloc, as dwindling majority groups often fear. They tend to form coalitions around different interests. However, rising minority groups are likely to act or vote as a bloc if they share a history of abuse at the hands of the declining majority group – like Shi'a Arabs did in Iraq, or Chechens and other national identity groups did in the USSR.

Since 2017, at least two overlapping demographic groups highlight claims of group abuse: African Americans, through #BlackLivesMatter, and women, through #MeToo. If my research holds true, expect African Americans and women to vote against the GOP in 2020. The GOP’s current policies at our national borders could only make conservative fears a self-fulfilling prophecy and may cause Latino Americans to start voting against the GOP as a bloc.

So if I’m right, the only way to avoid the kind of internal strife we have seen time and again in other countries is for federal and state governments to commit to a future of inclusiveness. That way, in 2050, when middle-aged white Protestant Christian males become a national minority, every American wins.

![]()

Monica Duffy Toft, Professor of International Politics and Director of the Center for Strategic Studies at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.