Larry Brand, University of Miami

Millions of gallons of water laced with fertilizer ingredients are being pumped into Florida’s Tampa Bay from a leaking reservoir at an abandoned phosphate plant at Piney Point. As the water spreads into the bay, it carries phosphorus and nitrogen – nutrients that under the right conditions can fuel dangerous algae blooms that can suffocate sea grass beds and kill fish, dolphins and manatees.

It’s the kind of risk no one wants to see, but officials believed the other options were worse.

About 300 homes sit downstream from the 480-million-gallon reservoir, which began leaking in late March 2021. State officials determined that pumping out the water was the only way to prevent the reservoir’s walls from collapsing. They decided the safest location for all that water would be out through Port Manatee and into the bay.

Florida’s coast is dotted with fragile marine sanctuaries and sea grass beds that help nurture the state’s thriving marine and tourism economy. Those near Port Manatee now face a risk of algal blooms over the next few weeks. Once algae blooms get started, little can be done to clean them up.

The phosphate mining industry around Tampa is just one source of nutrients that can fuel dangerous algae blooms, which I study as a marine biologist. The sugarcane industry, cattle ranches, dairy farms and citrus groves all release nutrients that often flow into rivers and eventually into bays and the ocean. Sewage is another problem – Miami and Fort Lauderdale, for example, have old sewage treatment systems with frequent pipe breaks that leak sewage into canals and coastal waters.

All can fuel harmful algal blooms that harm marine life and people. Overall, blooms are getting worse locally and globally.

The problem with algae blooms

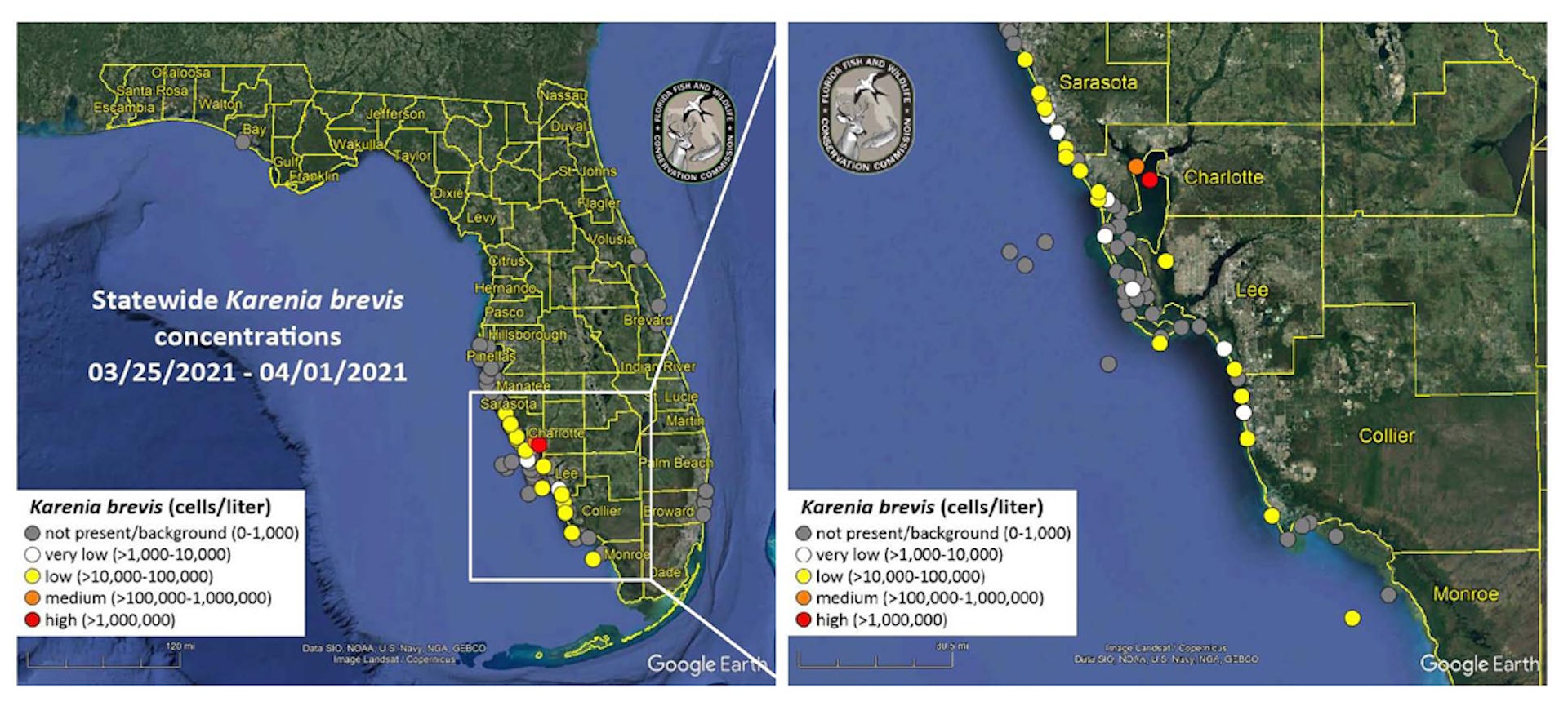

Just down the coast from Port Manatee, the next three counties to the south have had algae blooms in recent weeks, including red tide, which produces a neurotoxin that feels like pepper spray if you breathe it in. Karenia brevis, a dinoflagellate, is the organism in red tide and produces the toxin.

This part of Florida’s Gulf Coast is a hot spot for red tide, often fueled by agricultural runoff. A persistent red tide in 2017 and 2018 killed at least 177 manatees and left a trail of dead fish along the coast and into Tampa Bay. If the coastal currents carry today’s red tide father north and into Tampa Bay, the toxic algae could thrive on the nutrients from Piney Point.

Even blooms that are not toxic are still dangerous to ecosystems. They cloud the water, cutting off light and killing the plants below. A large enough bloom can also reduce oxygen in the water. A lack of oxygen can kill off everything in the water, including the fish.

This part of Florida has extensive sea grass meadows, about 2.2 million acres (8.9 billion square meters) in all, which are important habitat for lots of species and serve as nurseries for shrimp, crabs and fish. Scientists have argued that sea grass is also a major carbon sink – the grass sucks up carbon and pumps it down into the sediments.

Once the nutrients are in a large body of water, there isn’t much that can be done to stop algae growth. Killing the algae would only release the nutrients again, putting the bay back where it started. Algae blooms can remain a problem for years, finally declining when a predator population develops to eats them, a viral disease spreads through the bloom or strong currents and mixing disperse the bloom.

Agriculture runoff poses risks to marine life

The phosphate mining industry around Tampa is a large source of nutrient-rich waste. On average, more than 5 tons of phosphogypsum waste are produced for every ton of phosphoric acid created for fertilizer. In Florida, that adds up to over 1 billion tons of radioactive waste material that can’t be used, so it’s stacked up and turned into reservoirs like the one now leaking at Piney Point.

The reservoirs are obvious in satellite photos of the region, and they can be highly acidic. To get the phosphate out of the minerals, the industry uses sulfuric acid, and it leaves behind a highly acid wastewater. There have been at least two cases where it ate through the limestone below a reservoir, creating huge sinkholes hundreds of feet deep and draining wastewater into the aquifer.

Since saltwater had previously been pumped into the Piney Point reservoir, acidity is less of an issue. That’s because the seawater would buffer the pH. There is some radioactivity, but only slightly above regulatory standards, according to state Department of Environmental Protection, and probably not much of a health hazard.

But the nutrients are a risk. In 2004, water releases from the Piney Point reservoir contributed to an algae bloom in Bishop Harbor, just south of the current release site. In 2011, it released over 170 million gallons into Bishop Harbor again after a liner broke.

Another significant source of algae-feeding nutrients is agriculture, particularly cattle ranching and the sugarcane industry. Nutrient runoff from cattle ranches and dairy farms north of Lake Okeechobee end up in the lake. South of the lake, much of the northern third of the Everglades was converted to sugarcane farms, and those fields back-pumped runoff into the lake for decades until the state started cracking down in the 1980s. Their legacy nutrients are still in the lake.

The nutrient-rich water in the lake then pours down the Caloosahatchee River and into the Gulf of Mexico near Fort Myers, south of Tampa. That’s likely feeding the current red tide off the mouth of the Caloosahatchee River.

When water from the Everglades region’s agriculture is pumped south instead, huge blooms tend to appear in Florida Bay at the southern tip of the state. Some scientists believe it may be damaging coral reefs there, though there’s debate about it. During times that flow of water from the farms increased, reefs throughout the Florida Keys have been harmed. Those reefs have become overgrown with algae.

With the current red tide, the coastal currents have carried it north as far as Sarasota already. If they carry it farther north, it will run into the Piney Point area.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

![]()

Larry Brand, Professor of Marine Biology and Ecology, University of Miami

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.