Jamie Rowen, University of Massachusetts Amherst

As the nation takes a day to honor veterans, they are facing a deadly risk that has nothing to do with war or conflict: the coronavirus.

Different groups and communities have faced different degrees of danger from the pandemic, exemplified by the humanitarian disaster in India and the inequalities in U.S. health outcomes, vaccine distribution problems and outright rejection of vaccines. Veterans have been among the most hard-hit, with heightened health and economic threats from the pandemic. These veterans face homelessness, lack of health care, delays in receiving financial support and even death.

I have spent the past six years studying veterans with substance use and mental health disorders who are in the criminal justice system. This work revealed gaps in health care and financial support for veterans,

even though they have the best publicly funded benefits in the country.

Here are eight ways the pandemic continues to threaten veterans.

1. Age and other vulnerabilities

73% of veterans are over 50, and 89% are male.

The largest group served in the Gulf era, were exposed to dust storms, oil fires and burn pits with numerous toxins, and perhaps as a consequence have high rates of asthma and other respiratory illnesses.

The second-largest group served in the Vietnam era, in which 2.8 million veterans were exposed to Agent Orange, a chemical defoliant linked to cancer.

Age and respiratory illnesses are both risk factors for COVID-19 mortality. As of May 13, 2021, 258,078 people under Veterans Administration care have been diagnosed with COVID-19, of whom 11,941 have died.

Reluctance to be vaccinated continues to hamper full vaccination efforts, particularly in rural areas. The Veterans Administration has set up successful vaccine distribution sites that now administer to veterans, their spouses, caregivers and others receiving VA health care. Approximately 2.5 million of 19 million veterans have been vaccinated through the agency.

But demand is dipping from 75,000 appointments a day to 30,000, and President Joe Biden recently decided not to mandate vaccinations in the armed services, where vaccine rates remain low.

2. Benefits unfairly denied or delayed

When a person transitions from active military service to become a veteran, they receive a Certificate of Discharge or Release. This certificate provides information about the circumstances of the discharge or release. It includes characterizations such as “honorable,” “other than honorable,” “bad conduct” or “dishonorable.” These are crucial distinctions because that status determines whether the Veterans Administration will give them benefits.

Research shows that some veterans with discharges that limit their benefits have PTSD symptoms, military sexual trauma or other behaviors related to military stress. Veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan have disproportionately more of these negative discharges than veterans from other eras.

The Veterans Administration frequently and perhaps unlawfully denies benefits to veterans with “other than honorable” discharges.

Many veterans have requested upgrades to their discharge status. There is a significant backlog of these upgrade requests, and the pandemic added to it, further delaying access to health care and other benefits.

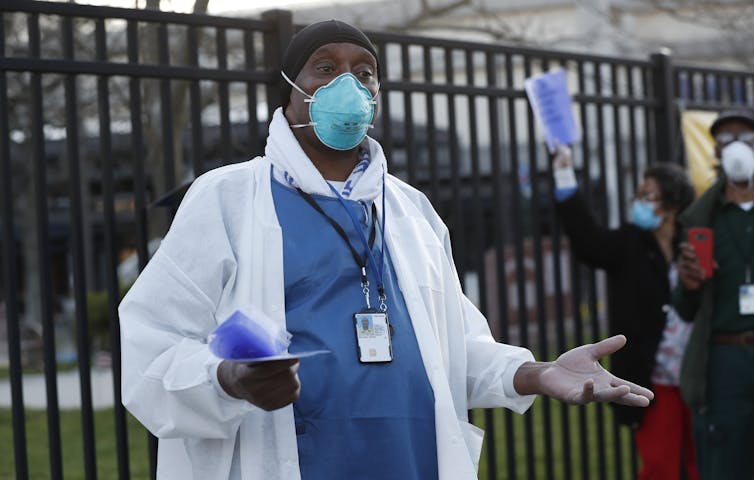

3. Diminished access to health care

Dental surgery, routine visits and elective surgeries at Veterans Administration medical centers have been postponed as individuals await the full reopening of offices. Veterans Administration hospitals are notoriously understaffed – just before the pandemic, the agency reported 43,000 vacancies out of more than 400,000 health care staff positions.

The pandemic added to these problems. An Inspector General report from fall 2020 found that 95% of Veterans Administration health centers are missing a key staff member, most commonly medical providers such as psychiatrists, primary care physicians and nurses, but also custodial staff necessary to keep facilities clean and sanitary.

4. Mental health may get worse

An average of 20 veterans die by suicide every day. A national task force is currently addressing this scourge.

The effects of the pandemic on veteran mental health are not yet clear. The VA continues to encourage digital mental health treatment since office visits remain limited. Suicide hotline calls by veterans were up by 12% on March 22, 2020, just a few weeks into the crisis. Recent information from the Department of Defense suggests the already troubling suicide rates have not changed, with Black and Hispanic veterans at higher risk.

5. Complications for homeless veterans and those in the justice system

The latest available data, from prior to the pandemic, documented 107,400 veterans in state or federal prisons, and 181,500 were incarcerated if we also include jails. While many facilities responded to the pandemic by releasing eligible veterans, there is a revolving door between time served and homelessness.

After years of declining rates of homelessness, there was a 0.5% rise in homelessness from 2019 to 2020. Before the pandemic, in January 2020, an estimated 37,252 veterans were homeless on any given night.

Thousands more veterans are under court-supervised substance use and mental health treatment in veterans treatment courts. More than half of veterans involved with the justice system have either mental health problems or substance use disorders.

Courts quickly moved online after state shutdowns, and many continue in this new mode. While often useful to meet treatment court obligations, online justice administration can be an obstacle for individuals looking for the camaraderie that came with meeting in person. Other challenges relate to access to technology and due process.

6. Disability benefits delayed

Veterans Administration office closures have exacerbated the longstanding backlog of disability claims, which more than doubled over the course of the pandemic. Approximately 200,000 veterans wait more than 125 days for a decision. Anything less than 125 days is not considered a delay in benefit claims.

There is a long delay for medical exams to determine disability benefits. As of March 2021, there was a backlog of 357,000 medical exams, nearly three times the backlog from February 2020.

The closure of the National Personnel Records Center, which houses the physical records frequently required to obtain benefits, led to an estimated 18- to 24-month backlog of 499,000 document requests. These documents are often necessary to receive medical benefits as well as military honors upon death.

7. Dangerous residential facilities

Veterans needing end-of-life care, those with cognitive disabilities or those needing substance use treatment often live in crowded Veterans Administration or state-funded residential facilities.

State-funded “soldiers’ homes” are notoriously starved for money and staff. The horrific situation at the soldiers’ home in Holyoke, Massachusetts, where 76 veteran residents died from a COVID-19 outbreak, leading to criminal charges, and the deaths of 46 veterans at an Alabama facility illustrate the risk that veterans in residential homes faced early in the pandemic.

8. Economic catastrophe

There are 1.2 million veteran employees in the five industries most severely affected – mining, oil and gas extraction; transportation and warehousing; employment services; travel arrangements; leisure and hospitality – by the economic fallout of the coronavirus. Veteran unemployment was at 3.5% before the pandemic and rose to 6.4% by September 2020.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

A disproportionately high number of post-9/11 veterans live in some of the hardest-hit communities that depend on these industries and had even higher rates of unemployment than their nonveteran peers as well as other veteran cohorts. Many veterans may face evictions when the national moratorium on evictions lifts on June 30, 2021.

Military spouses are suffering from the economic fallout, as are children affected by school closures.

With veterans, many of the problems they face now existed long before the coronavirus arrived on U.S. shores.

But with the problems posed by the situation today, veterans who were already lacking adequate benefits and resources are now in deeper trouble, and it will be harder to answer their needs.

Editor’s note: This is an updated version of a story that originally ran on April 16, 2020.

![]()

Jamie Rowen, Associate Professor of Legal Studies and Political Science, University of Massachusetts Amherst

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.