When oil and gas companies took to Twitter during the first half of the U.N.’s Glasgow climate conference, they often presented themselves as part of the solution to climate change and talked about energy security.

In many ways, their messaging on social media provides a window into how these companies want the public to see the future.

For example, while policymakers talk about a “low-carbon economy” – indicating that while there will be carbon in our lives, it will be as low as it can be – the tweets from some oil and gas accounts instead use the phrase “lower carbon.” A “lower carbon” economy is a far more nebulous goal that can involve continuing significant levels of fossil fuel use well into the future.

Social media is just the public face for these companies, many of which have lobbyists at the climate conference. Behind the scenes, the industry continues to invest in extracting fossil fuels that are driving climate change, and its CEOs have made clear that fossil fuel production will continue for decades to come.

Fossil fuel industry misdirection

In 2015, when a colleague and I first researched what key fossil fuel trade groups were saying on Twitter about climate solutions during the landmark COP21 summit in Paris, we found they were largely promoting a narrative that the Obama administration’s climate policies lacked domestic support – despite public opinion research indicating otherwise.

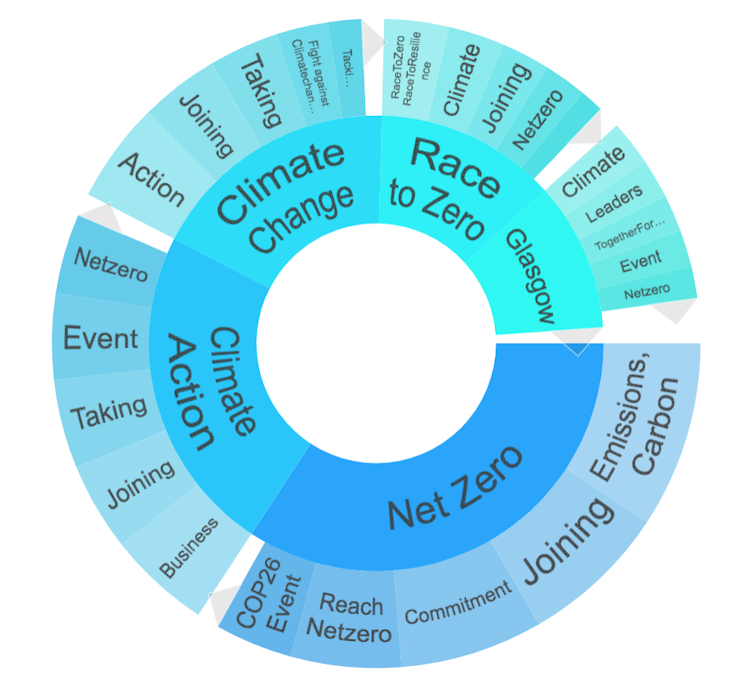

This time around, using the consumer insights software Brandwatch, I studied recent English-language tweets from top oil, gas and coal producers globally during COP26, as well as from the American Petroleum Institute and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Executives from four oil companies, API and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce had been grilled by members of the House Committee on Oversight and Reform on Oct. 28, 2021, about their roles in the spread of misinformation about climate change.

The corporate accounts today present themselves as part of the solution – for example, talking about renewable energy and electric vehicle charging infrastructure. Low-carbon projects are only a small part of the oil companies’ portfolios, though. And the same companies fueled the problem while knowing the risks.

This subtle form of misinformation, which scholars have called “fossil fuel solutionism,” involves cherry-picking data and talking points.

For example, a BP tweet saying that reducing methane emissions is key to “slowing the rate of warming” omits an important point. While addressing methane leaks from fossil fuel infrastructure is an important step, a fundamental shift away from fossil fuels is considered crucial.

The International Energy Agency predicts upstream oil and gas investment will increase by about 10% this year, though not to pre-pandemic levels, while clean energy investments remain “far short of what will be required to avoid severe impacts from climate change.”

The American Petroleum Institute, in particular, has been posting on themes of affordable, reliable, American-made energy and concern over gas prices while also claiming that restricting oil and gas drilling on federal land “would be counterproductive to our shared goal of reducing emissions.” API’s argument is that restrictions would increase use of coal and foreign imports.

Several posts employ a subtle shift in language to talk about technological innovation and energy transition in terms of “lower carbon,” rather than the more commonly heard discourse on “low carbon.” This shift appears to be recent. In the past, the theme appeared in discussions of natural gas as a “bridge fuel.”

The black box of digital advertising

These accounts are only one piece of the industry’s social media ecosystem. The paid advertising footprint of oil and gas is much larger. It is also harder to track, especially on Twitter.

According to research by the nonprofit think tank InfluenceMap, the industry deploys Facebook ads at key political moments. For example, during Oct. 16-22, 2021, in the lead-up to the Congressional hearing with the oil CEOs and the recent elections, ExxonMobil spent $565,099 on Facebook ads targeting U.S. users.

Climate journalists Emily Atkin and Molly Taft found the lower-carbon theme in fossil fuel advertising within recent political newsletters.

For example, related to the U.N. climate conference, ExxonMobil is sponsoring the political news site The Hill’s energy and environment newsletter, along with the American Petroleum Institute. Some researchers refer to that as “fossil fuel corporate propaganda.” This amounts to a strategy to enhance corporate legitimacy while at the same time downplay the need for government regulation.

Part of a wider problem

The structure of online social networks is characterized by polarization and echo chambers that allow misleading climate change content to spread.

An example is a tweet that got a lot of impressions at the start of COP26. It was a post from conservative commentator Ben Shapiro containing a logical fallacy in attempting to discredit the U.N.‘s climate work. Shapiro came in third for average reach during week one of the summit within a sample of climate change tweets, following only President Joe Biden and former President Barack Obama.

Social media companies have been under scrutiny for facilitating the wide spread of misinformation on several topics, including climate change.

In one analysis of Facebook pages, the environmental group Stop Funding Heat found nearly 39,000 posts with misinformation over eight months on 195 pages known for blatant climate misinformation. It also found a 76.7% increase in people interacting with those pages compared to the previous year, suggesting Facebook’s algorithm was sharing the content widely.

Taking a cue from climate disinformation researchers, Twitter launched what it calls “pre-bunks” – sending accurate messages out in search, explore and trends lists. But it didn’t plan to stop people and bots posting climate misinformation or label it as such. In the first 10 months of 2021, Twitter says climate change was mentioned 40 million times on its channels.

[Over 115,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

![]()

Jill Hopke, Associate professor, DePaul University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.